The deconstruction of a Semiconductor Cycle

What can be learned from the Q3-25 results of the Semiconductor Industry?

Guest Article written by Claus Aasholm, Semiconductor Business Intelligence

The Semiconductor industry is deep into what likely will be known as the 2026 upcycle, that is, if the semiconductor cycle still exists by then. The Semiconductor revenue is scheduled to peak this quarter if it follows the normal 16-quarter cycle.

For almost a year, the monthly growth rates have been above 20% YoY and the WSTS reporting for October was 22.9% above October last year.

If you are the CEO of a Semiconductor Company that subscribes to WSTS data and your company is growing by less than 22.9%, you are losing market share in Semiconductors. You should not be wasting your time reading my blog; you should be explaining yourself to the board.

If you are working in a product division with less than 22.9% YoY growth, you should not expect to be showered with promotions and Restricted Stock Units. You should be worried about the HR lawyers using AI to draft your PIP.

But this is not how the world works anymore, nor is it fair.

You subscribe to the WSTS numbers, then deduct all the markets you don’t participate in or rather, not participate successfully in.

Get rid of the Nvidia number - that is not our market. Deduct memory, that is not our game. Throw out networking, we don’t participate in that field. Let go of Analogue; we are purely a digital company.

All of that is a reasonable exercise to get to a meaningful number, but make sure you complete it at an appropriate level.

If you keep deducting until you have a number set that your ego can handle, you might understand that you are gaining market share in products only sold to left-handed, lesbian sumo wrestlers.

I have been part of that game, and it is full of inflated titles and fragile egos that cannot handle data that suggests a decline in market share. The outcome of these futile exercises is a wonderful market where everyone is winning. So much winning that it is tiring. So much corporate candy floss.

For sure, there are companies in the semiconductor industry that are tired of winning. Jensen Huang recently told employees that the company is in a no-win trap:

“If we deliver a bad quarter, it is evidence there’s an AI bubble. If we deliver a great quarter, we are fueling the AI bubble.”

But in average companies, the products and divisions are average. Most semiconductor companies are not invited to the AI party. They are desperately trying to find ways to participate in the AI revolution, even if that means designing the Hallucination-Proof AI LED driver.

It is reasonable to ask the question, who is measuring themselves against the WSTS number anymore? The Semiconductor industry has evolved into a mix of business models and products serving submarkets that behave differently.

If you have made it this far and are working in a Semiconductor Company or a division genuinely interested in understanding the size of the market you are in, you have my deepest apologies for my prior comments. My tirade is pent-up anger for the entire analyst community for what they have had to endure.

If you stay with me a little bit longer, the alcohol to caffeine ratio in my blood will become sufficiently favourable to ignite my analytical neurons, which can give you more relevant insights into the semiconductor market than a top-line number can do.

It is not only the semiconductor companies that are struggling to relate to the WSTS numbers. Suppliers to the Semiconductor industry are wondering whether the new AI chips are made entirely of air, which the revenue numbers of semiconductor gas companies will refute.

My readers will know that I boil strategy down to three simple questions: What is happening? What can we do about it? What are we doing about it?

The first question concerns what happens in the market and its surroundings. If that is defined too narrowly, you are going to miss the truck that is headed straight for you, and you risk making subpar decisions.

A good strategy is always founded on a good map of the market, and a vision of where it is headed, and the map should be as neutral and unbiased as possible (rare qualities these days).

That’s where I come into the picture. I am an analyst, and I really don’t care about your compensation exercises to make your puny division look larger or your hallucinations of growth. For me, there is no good or bad data - I follow the data where it goes and share my observations. I am not an acolyte of the Circular Collapse Cult nor have I converted to Cudaism. While I am invested in Semiconductor companies (it would be stupid not to), my average holding is 10 years plus, and I never bet for or against the companies I write about. You can go to Michael Burry if that is what you want.

With my boilerplate out of the way, it is time to dig into the analysis.

The deconstruction of a Semiconductor Cycle

While I don’t spend much time contemplating the WSTS method for arriving at its top-line number, most of my clients are asking me to reconcile my Semiconductor Market Revenue with WSTS's top-line number.

I am measuring all device revenue billed in the Semiconductor market. A device is a single unit, chip, or subsystem, and the market refers to sales in free trade. This excludes all foundry revenue, including production for Apple and Google. While these products are certainly semiconductors, they have not been on the market and therefore do not have a billing number.

My Semiconductor Market Revenue gets good alignment with WSTS, if I make a couple of assumptions:

- All Nvidia revenue is Semiconductor Device revenue

- I allow HBM revenue to be counted twice. First, as HBM revenue is sold to Nvidia and other AI companies, and secondly, when it is resold as an AI server board with the same HBM mounted.

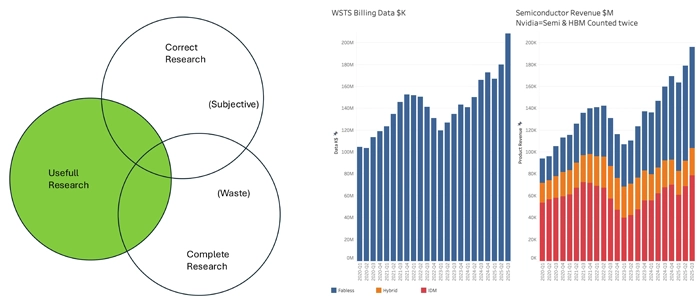

I don’t spend time considering what is “right” or “wrong” research. That is a discussion I left with my corporate life. Without a boss, I have the freedom to spend my time on useful research.

Should you disagree with my definition of useful research, I will not stand in your way of doing your own research.

In this article, I will use the definition that best aligns with the WSTS numbers. The result can be seen below.

My Semiconductor Market Revenue method is developed to derive insights, not as an accounting exercise, and I can cut my numbers in many ways to achieve what I want.

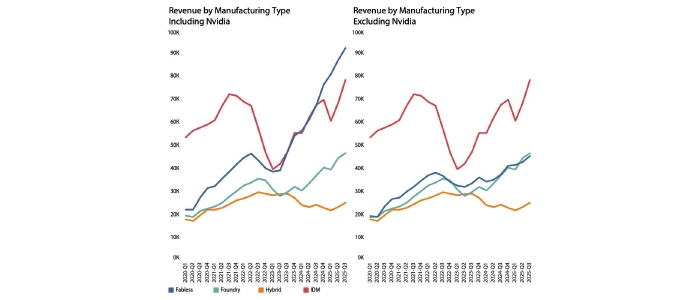

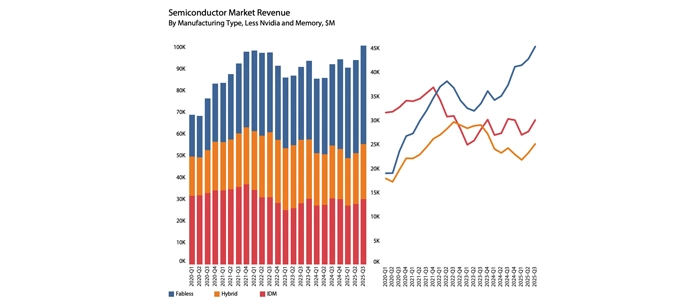

A high-level analysis helps divide semiconductor companies into three main business models. The traditional Integrated Device Manufacturer (IDM) model, which designs and manufactures semiconductors in-house, is increasingly being overtaken by the Fabless model. At the same time, several companies have opted for a hybrid of the two business models.

As can be seen, the revenue from the fabless model is outgrowing the other models, and it is no secret that Nvidia’s revenue drives this.

Just knowing that something is going on is not the same as understanding how fast or how much. To get to something meaningful, we need to begin deconstructing the number and understand its details.

Adding the foundry revenue to the chart shows that excluding Nvidia from the Semiconductor Market Revenue gives a very similar trajectory for the revenue of the Fabless semiconductor companies and their foundry partners. The foundry revenue is slightly delayed and is growing faster than the non-NVIDIA fabless revenue.

The Market Revenue of all three manufacturing are increasing. Even the Hybrid revenue has now experienced two solid quarters of growth and is up 15% from its low during the down cycle.

It is also clear that the cycle is not in sync across the manufacturing models. The hybrid model is now completely detached from the cycle.

The semiconductor cycle has its origins in the IDM sector, specifically in the revenue of the Memory Companies.

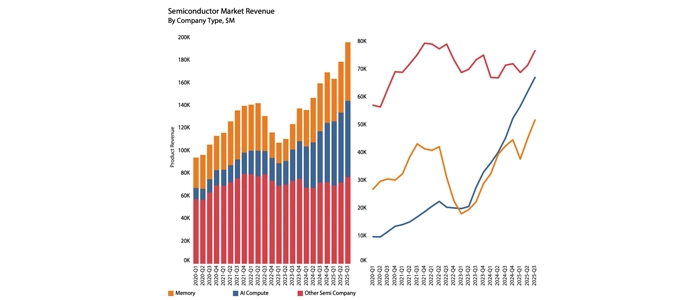

To observe this, I use a different deconstruction, dividing the Semiconductor Market Revenue up into AI Compute Companies, Memory Companies and others.

Here, the strong cyclicality of memory can be observed, and the current cycle is well aligned with the last peak in 21/22.

What needs to be understood about the Memory market is that the most prominent players are not decreasing their production during the downturn. The production is always on. Even when producing at a loss.

What causes the cycle are the increases or decreases in memory pricing. This is also what creates the broader cycle: expensive memories depress, in particular, PC, Tablet, and Smartphone sales, while cheap memories do the opposite. This cycle, however, is different, as AI now consumes more memory and is less price-sensitive than the other product categories. You can read more about the end ot the 2026 cycle here: The end of the 2026 Semiconductor Cycle.

For most semiconductor companies, the next logical step is to remove both Nvidia and Memory from the analysis to observe the broader market's trajectory.

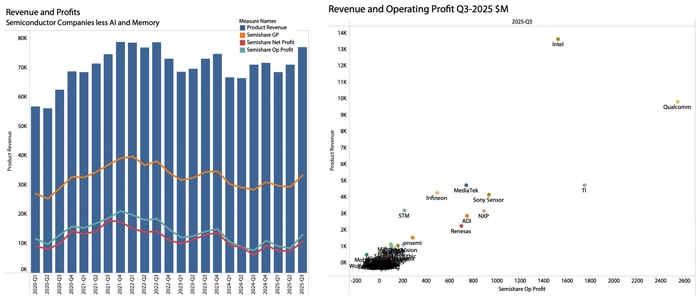

This is a very different market reality from the one that WSTS and SIA are portraying. The strong 20/21 up-cycle is not repeated in the 23/24 up-cycle. In this analysis, I have only excluded 4 meaningful companies: Nvidia, Samsung Memory, SK Hynix and Micron, and for the rest of the Semiconductor companies, the market is virtually flat over time.

The last step before further analysis is to remove the other 3 AI Compute Companies, AMD, Broadcom and Marvel, to get to what I will designate as the core semiconductor market.

The core semiconductor companies are experiencing a totally different reality than the top-line AI bonanza seen in the WSTS numbers.

While the downturn from the peak in Q4-21 has been modest at 16%, with a trough in Q2-24, revenue has increased by a healthy 8.4% in Q3-25, which is now only 2.3% below the overall peak.

Also, the profits have jumped in Q3-25, with Gross, Operating, and Net Profits increasing by 13.4%, 55.3%, and 44.2%, respectively. While these quarterly growth rates are strong, the profitability of the Core semiconductor companies is still some distance away from the peak, one quarter away from what would generally be the peak.

The harsh reality is that growth has stalled, and profitability is at a level similar to 5 years ago.

The most significant components of the core semiconductor market from a revenue and operating profit perspective can be seen above.

Given that Intel is the most significant component in the Core Semiconductor Market and the company’s recent troubles, it should be excluded. While it changes the curves slightly, it does not change the overall conclusion of quite mediocre growth rates.

This map also highlights that the semiconductor market is relatively concentrated, with 10 core companies plus the three memory and 4 AI companies I have excluded. The total number of Semiconductor companies I track is close to 100.

We are now getting closer to a growth number that is more meaningful to the bulk of the semiconductor companies.

The quarterly median growth rates for the most prominent companies are shown below, with significant improvements in Intel's and Qorvo's profits.

For the top companies, revenue growth was 6.25% and operating profits improved by 11.8%. For the entire core group, the quarterly median revenue growth was 5.9% while the operating profit growth was 12%.

The bands represent the quartiles, meaning that 50% of all company results fall within each band.

For YoY growth, the median for larger companies is -0.7%, while operating profits improved by 3%. For all semiconductor companies, the median growth was substantially better, at 13.9% in revenue and 18% in operating profit.

From the chart, it can be seen that it is predominantly the hybrid semiconductor companies that are pulling the results down, except the analogue hybrid companies, ADI and TI.

Once again, this shows that the one-size-fits-all top-line Semiconductor Market Billing number fits no one. A deeper analysis is needed to understand if your business is running above or below par.

I understand if you are too busy for strategic work. The day is full of bits and bytes and I/O, and you are constantly pushed for a bookings report. But every once in a while, I recommend lifting your gaze from the next hour to the future. Your business might depend on it.

After investigating Q3-25 revenue and operating profit growth, it is time to go a bit deeper to see where the semiconductor industry is headed.

The Inventory situation

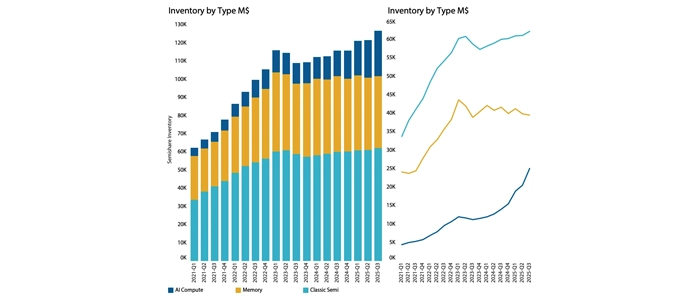

To understand the immediate future of the Semiconductor industry, it is helpful to perform an inventory analysis. Rather than performing the study according to the manufacturing model, the current market situation, driven by AI Compute consumption and the rising price of memory, calls for choosing this as the analysis dimension.

The analysis reveals three quite different trajectories for the three types of companies.

While the rapid increase in AI companies' inventory might not come as a surprise, it accounts for all the increase since the last peak.

The declining inventory of memory companies could also be expected as the current hot move into a red-hot memory market reduces inventories.

It is worth noting that inventories are carried at cost, so an inventory analysis is not disturbed by the high margins of AI or the increasing margins of memories. This means an inventory analysis provides better insight into the activity levels of different product types than a revenue analysis.

Earlier, it was seen that the AI companies accounted for 34% of the revenue but only 19% of the combined inventory in the Semiconductor industry. While I understand that the different manufacturing models produce different inventories and that they are not comparable in every dimension, it is still a worthwhile exercise to conduct.

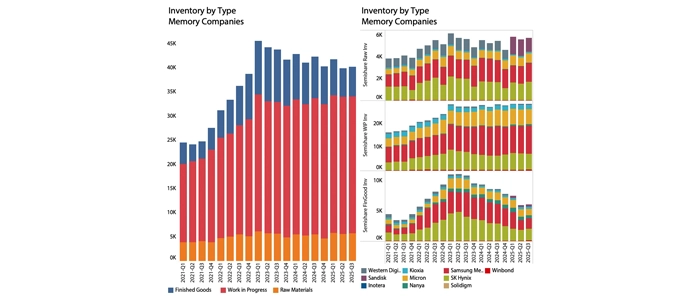

The inventory of the memory companies can be seen in detail below:

The first observation is that the finished goods inventory has been in decline since the last cycle and is likely near its physical minimum due to the time required for physical transportation.

The Work in Progress inventory for the Memory companies has been flat since the last peak cycle. This represents the manufacturing activity measured at cost. While there has been some decline in the cost per bit, it is clear that the expansion in manufacturing seen before 2023 has dwindled to a level that looks more like maintenance.

This is what is causing the current memory pricing to explode. The increase in AI memory demand has to be accommodated with limited manufacturing expansion.

The price increases were already apparent in Micron's September results and have only gotten worse since then.

While the raw materials inventory is not the same as material consumption, it is a good proxy, and this is also flat for the memory companies.

This is not only happening in memories but is a broader industry change observed in this cycle.

The current cycle is a profit cycle to which the semiconductor materials companies have not been invited.

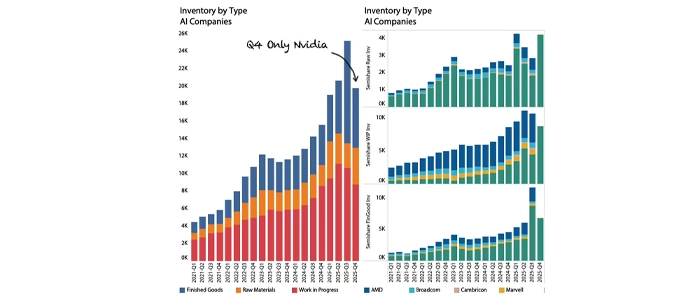

Turning the attention to the AI companies' inventory reveals a radically different situation. I have added Nvidia’s Q4 inventory, as this has been changing significantly.

While Nvidia's finished goods inventory shot up in Q3-25, the decline in Q4 suggests this was due to shipment adjustments, as confirmed by Nvidia's revenue, which was lower than the overall growth curve in Q3-25.

The dramatic increase in memory pricing is evident in Nvidia's raw inventory. This is a combination of HBM and other high-end memory for Nvidia's server production, and since HBM pricing is long-term, the effect is likely skewed towards non-HBM memory.

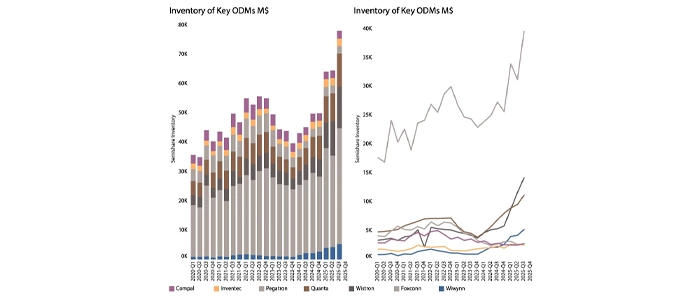

This is mirrored in the Work In Progress inventory, which has also increased dramatically. An interesting wrinkle in WIP inventory is the relatively large AMD inventory. The CPU business for both PC and Datacenter, along with Xilinx, is likely the reason behind this. Nvidia is “parking” some of its WIP inventory with the large ODMs responsible for acquiring some of the server parts. As shown below, this has impacted the inventory of a selection of ODMs.

The worker bees of Taiwan are certainly busy making Nvidia servers.

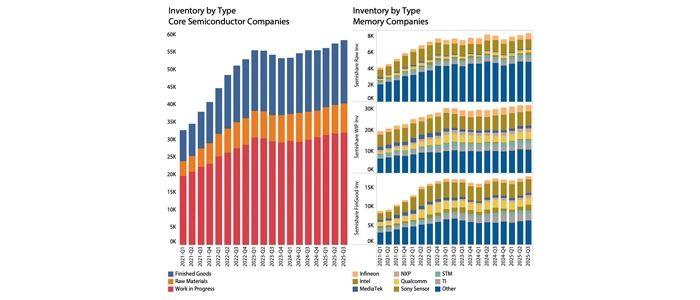

Finally, it is time to investigate the inventory of the core semiconductor companies. As shown earlier, the Core Semiconductor companies had a good quarter but are still below their last peak, and profitability remains weak.

The profitability of the core semiconductor companies is impacted by the high finished goods inventories that have been creeping up, as are the manufacturing activity levels reflected in the increasing WIP inventory.

The core semiconductor companies are in a weak recovery, trying to gently increase manufacturing levels while balancing finished goods inventories.

This is the reality of 90% of the semiconductor companies, and the situation is even worse for the supply chain.

What about China?

A significant reason for the soft recovery is the rising geopolitical activity under shifting US administrations. The embargoes on the Chinese semiconductor industry have been marred by random drive-by tariffs that have made the supply chain very wobbly and sent it towards calmer waters.

The supply chain, in general, is sufficiently resilient to withstand the tariffs, and the impact has remained in the low single digits.

The Chinese semiconductor industry is still dominated by a few large private companies, especially in memory, making it difficult to track the market.

According to WSTS, the Chinese semiconductor market is growing less than the global market. In 2020, the Chinese market accounted for 36% of the worldwide market. It is now at just under 27% after the AI revolution has impacted the market.

The Chinese Semiconductor production, however, has tripled since the beginning of 2019 and is now able to supply an estimated half of the domestic market.

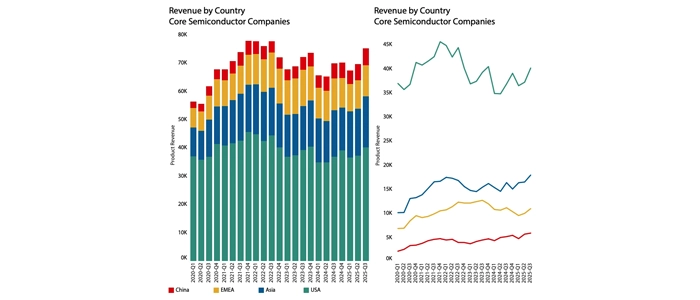

Slightly under a quarter of Chinese Semiconductor revenue is visible through public companies and is shown below, compared to the revenue of the core semiconductor companies.

Outside AI and memories, the Chinese companies have been gaining market share against the core Western companies, while the US and EMEA companies have lost share.

The embargos and tariffs might have made life difficult for the Chinese, but the trade barriers have also protected the Chinese companies from competition.

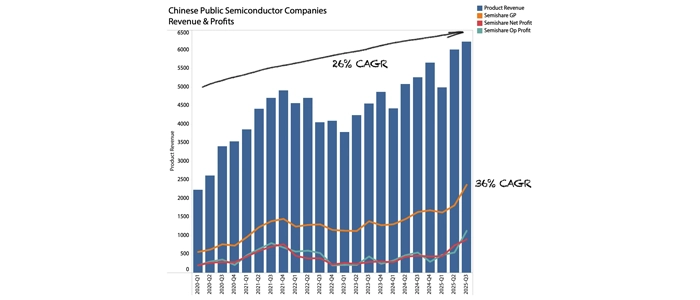

In the same period, as the Chinese home markets have been soft, the public Chinese Semiconductor companies have had a party. The revenue has grown at over 26% CAGR in the same period, as the total revenue of the Core Semiconductor companies have grown at under 3 per cent.

Coinciding with the tariffs imposed by the Trump administration, the profitability of the Chinese public companies has increased dramatically. If there is a causal connection, I will leave it to your belief system to decide.

Conclusion

For many years, semiconductor companies measured themselves against a top-line Semiconductor Device billings number to gauge overall performance. The 4-year semiconductor cycle also gave semiconductor companies some predictability, helping them navigate the investment cycle and know when to reef the sails.

I remember a senior leader telling me that market research was a waste of time, since things would eventually go back up. But those days are over. Things might not go up again.

The AI revolution has broken the Semiconductor cycle, and there are no signs of an immediate return to the good old days. The top-line revenue growth is mainly AI-driven and provides no nutrients for the supply chain. Semiconductor supply companies are still 10% below their peak revenue, while semiconductor revenue has grown 37% in the same period.

While the semiconductor supply chain has been able to sustain the AI revolution without too much trouble, this has been temporary, as memory companies have faced soft demand outside HBM due to rising Chinese memory production. This has now come to an abrupt halt, and memory pricing is exploding as supply has become inelastic. Price increases do not lead to production increases. The current increase in memory production was established several quarters ago in a soft market.

Outside the AI and Memory companies, the 90% core semiconductor companies are wondering what is going on. After a delayed recovery, the core semiconductor companies have had a couple of good quarters, but the supply situation in memory is already about to impact demand.

The AI memory demand is not very price-sensitive. The large hyperscalers and the AI native customers are now investing over $100B a quarter into new datacenter infrastructure, and memory pricing is not going to limit that significantly.

This is not the case for the other markets, depending on the memory supply. The PC and smartphone markets are essential to the broader recovery, and demand is sensitive to memory pricing.

The frail core semiconductor cycle is at risk of dying in its cradle.

We are at the brink of a new market reality that calls for strategic action. The old market logic is breaking down, and it is time to adapt to this new reality.

The 10% of the semiconductor companies that are in AI and Memory will have their own cycle - currently just up, but eventually something will happen. In the shadows of Mount AI, the other semiconductor companies might have to prepare for another downcycle before the inventories from the last cycle are consumed.

When is now a good time to review your strategy?

Claus Aasholm will be speaking at the upcoming Evertiq Expo events in Zurich (April 23), Kraków (May 7), and Lund (May 21). Attendees interested in his semiconductor market analyses will have the opportunity to hear his perspectives in person and engage with the topics discussed in this article. Registration for all three events is now open.