When electronics infiltrates art

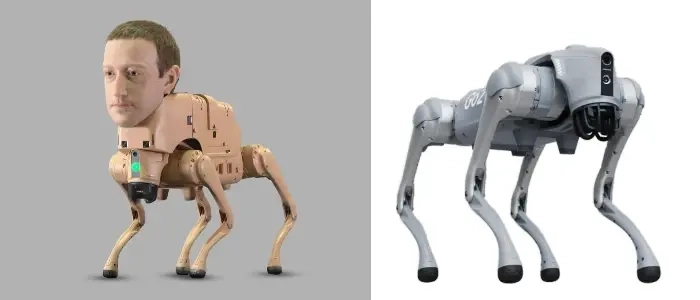

At Art Basel Miami 2025, the main stars were not paintings, sculptures or light installations. Instead, a group of robot dogs confidently patrolled the exhibition floor, moving like the household pets of modern billionaires. This would hardly be unusual, if not for one detail: each dog wore a hyper-realistic silicone mask depicting the most recognizable figures in the tech world. Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg and Sam Altman suddenly appeared in canine form.

The installation is titled Regular Animals and was created by Mike Winkelmann, better known as Beeple. His goal was to examine how technology, algorithms and large media platforms shape the way we see, consume and produce images. Instead of a brush or a chisel, we are now dealing with a machine, a system, artificial intelligence, vast data resources and a walking subject that literally generates art.

The robot dogs take photos of visitors and then, in a manner impossible to overlook, “excrete” the final result: a physical print paired with an NFT. Beeple dislikes subtlety, so each print is labelled with a pleasantly technical description: Excrement Sample. The entire installation balances between satire and artistic manifesto. Who is actually producing images today? The artist? The machine? Or perhaps an algorithm owned by a wealthy platform operator who sees more than any collector ever could?

The installation operates like a mobile art factory. Motion sensors, cameras and generative software take over the tasks that once belonged to a single artist: framing, observing and interpreting reality. The robot becomes the eye, the hand, and the processing engine.

Beeple provides the concept. The hyper-realistic masks were made by Landon Meier, a well-known mask designer and special effects artist. There is still no official information about who engineered the robotic bodies themselves, although their silhouette closely resembles the four-legged units manufactured by Unitree Robotics. The collaboration between the artist, mask designers, animatronics specialists and engineers represents a new model of art production: collective, technologically complex and fully interdisciplinary. Yet one question remains: are we overlooking the contribution of the people or companies without whom this “artwork” would never exist?

Not only is the object of artistic consumption changing, but also the role of the artist. In the past, collectors bought skill, craft and an individual gesture. Today, collectors often acquire entire production systems: algorithms, processes, datasets and, in some cases, the physical machine itself.

Perhaps the successors of old artistic workshops are not artists at all, but engineers. Just as the best sculptural or goldsmith workshops once worked for a master, today interdisciplinary teams create the physical fabric of the work: construction, motion control, sensors, vision systems and software integration. Beeple designs the concept, much like historical masters once designed altars or chapels, but someone else gives that concept a material body. The tools have changed: not chisels or pigments, but microchips, code, actuators and thermal cameras. And yet the physical work — even if distributed across a team — remains fundamental. The artwork does not exist without those who built it.

One thing is certain: Beeple’s robot dogs are not merely an installation. They are a sign of the times. When electronics cease to be just a tool and become art themselves, a work no longer has to hang on a wall. It can move among people. And occasionally, it comments on them with unsettling accuracy.