One in a Million. People used to be our greatest strength

In this first article of Evertiq’s new expert column series, Claus Aasholm – seasoned technology executive and strategist – shares his perspective on the trends, challenges, and breakthroughs shaping the global electronics industry. Drawing on decades of hands-on experience, Claus offers sharp, thought-provoking insights that go beyond headlines and buzzwords. Expect analysis that connects the dots – and challenges the status quo.

Author: Claus Aasholm, Semiconductor Business Intelligence

I have been fortunate enough to be part of the most amazing industry, and even more fortunate to stay relevant as it has evolved to dominate the global economy.

As a young man, I earned my badges in various areas of the supply chain and diverse fields, including corporate business areas. After many years of working in the business, it was time to lift my gaze from my feet to the horizon. It was time to work on the business rather than in the business.

In what began with research in the markets my employers were in, it quickly expanded to other semiconductor markets and eventually to the entire supply chain. If I had known how much work it would require, I would not have embarked on this journey. However, having completed the tricky part (I hope.. ), I can now focus on the analysis.

Rather than leading with opinion, I lead with data and facts, and my tools enable me to conduct analysis on the fly and create solid foundations for strategy in minutes, not days.

While industry and market analysis is often conducted within the corporation, it is usually assigned to low-level employees in an appendix organisation that carries no corporate power. The organisation assumes that intelligent people rise to the top, so business analysts are delivering insights to superior beings who know what to do with them.

The reality is that the climb of the hierarchical ladder is predominantly a political game of getting access to the “ingroup” of the current leadership team.

I say this as some of the most wonderful minds I have worked with have been analysing the corporate data while being largely ignored by middle management and barred from senior management. You would think that the CEO has access to all the data, but often CEO’s are kept in an isolated bubble and only fed facts curated by the product divisions and corporate staff functions.

These data analysts possess valuable insights about the corporation long before the CEO, and they often acquire this knowledge early. However, they have a low score in corporate power and are generally not very impressed with the management layers above them.

As one of my favourite data people put it: “I don’t waste my time on people who don’t know the difference between median and average”, I know he will be reading this and chuckling.

To gain credibility, you must leave the organisation and the political environment that distorts the facts.

The organisational structure of a corporation is built on a specific vision of the world, and as such, it is a construct that will compete with other visions of the world.

As an example, the Intel organisation is built around the vision of the Client business being the primary driver of Intel’s future, which has suffocated other visions more aligned with the real world.

While people are often accused of being resistant to change, I find it more relevant to accuse the organisational structure of being resistant to change. This is exemplified in the kinds of facts the organisation prefers to use and the sort of facts it would like to bury.

The data people are instructed to create dashboards with data deemed palatable to the senior leadership team, while curiosity is considered wasteful or downright counterproductive.

The Corporation fights change like the body fights a virus.

While there are many positive aspects to having an organisation, it should never be considered a corporate relic; instead, it should constantly be challenged.

I will let you have your vision of the corporation. Still, you may not be surprised to learn that, for me, it is necessary to be uncorporated to study the supply network of the Semiconductor industry.

Even though I was outside the Semiconductor companies, I still felt part of the industry and part of the soon-to-be 1 million people of the core Semiconductor industry. I would still be one in a million.

But something has changed. I might never become 1 in a million.

This is where my story about my almost a million colleagues begins, and the story of the old semiconductor industry ends.

The greatest strength of the Semiconductor Industry?

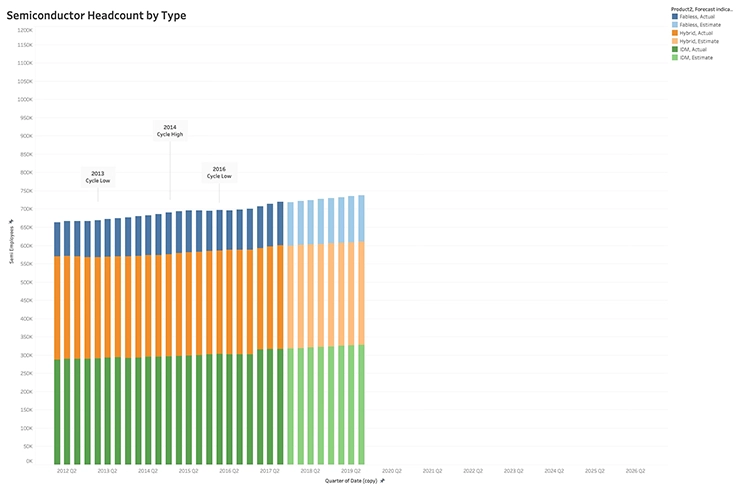

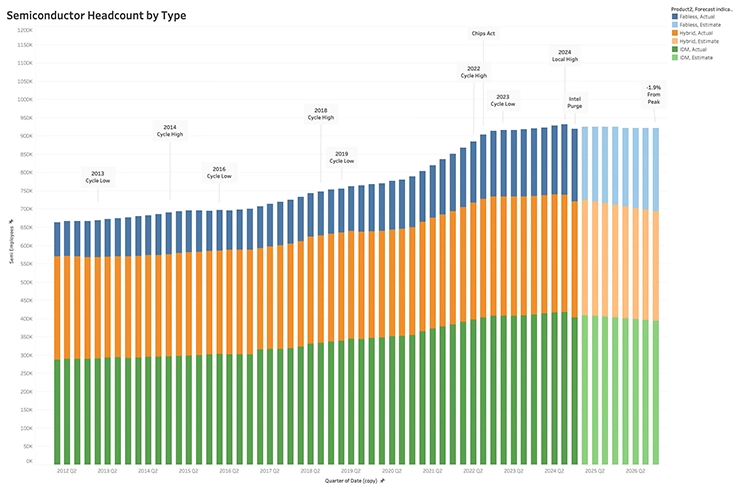

While the revenue of semiconductor companies had faithfully followed the well-known 4-year semiconductor cycle (Ripples and Tsunamis in the Semiconductor Supply Chain & Evertiq Keynote Presentation) and the industry had settled on an 8% CAGR growth rate in the mid-teens, the industry headcount followed a different trajectory.

It is not surprising that a high-tech industry like semiconductors increases productivity over time, as demonstrated by the much lower 1.3% CAGR of headcount.

Although the 2016 downcycle somewhat impacted headcount growth, it remained generally resilient and continued to increase over time. The forecasts for 18 and 19 pointed in the same direction.

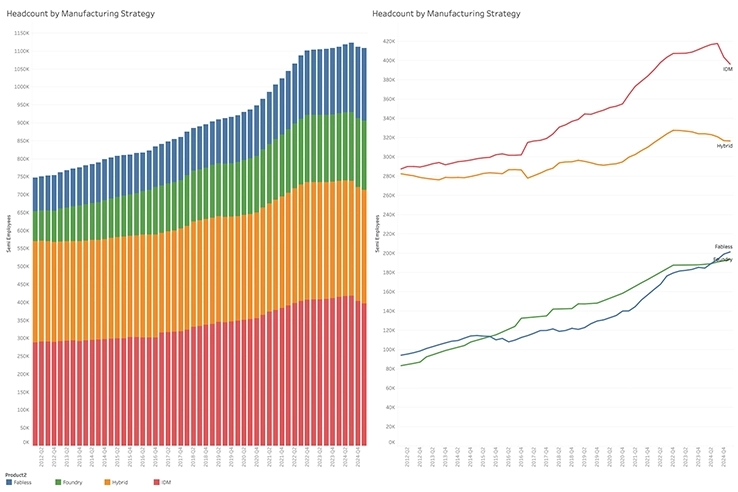

Generally, all three operational models of semiconductor companies followed similar growth rates in headcount.

Overall, this is a reasonably predictable phase of the industry’s life cycle, and companies base their operational strategies on managing the cycle and timing of Capital Investments in new Capacity. We could call this period the good old days.

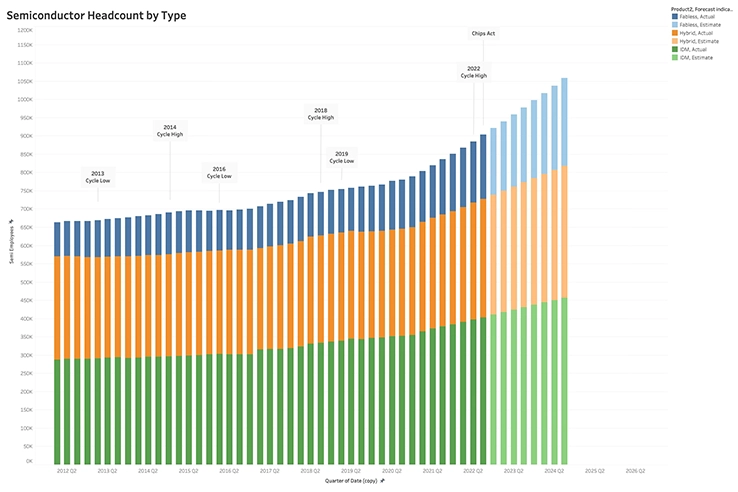

Just after the 2022 Cycle high, the semiconductor headcount was on a different trajectory, and I was just a few quarters away from becoming one of a million in the semiconductor industry. An impossible dream when I joined the industry back in the eighties.

The headcount expansion had increased to a 7.6% CAGR, just a fraction away from the industry's revenue growth. This appeared to be the beginning of a new, glorious era for semiconductor people and their employment prospects.

It became even better when the Chips Act was ratified in late 2022. Companies did not have to worry about boring details like Revenue, profits and operating cash flows. With billions flowing from the Chips Act, chipmakers found themselves comfortably latched onto the government teat — no elbowing required.

When analysing the impact of recent US government activity on the semiconductor industry, I often get accused of crying chihuahua when I thought I was crying wolf. Still, the wolf might not be eating the cats and dogs, but it is eating the jobs.

The Chips Act and associated embargoes and tariffs are the weapons in the Chip Wars between the US and China. While these government interventions rarely lead to the desired outcome, they always have an impact, as illustrated below.

Following the Chips Act and the cycle's low point in 2023, the semiconductor industry's headcount continued on a lower growth trajectory of 1.6% CAGR. The most recent quarter was impacted by Intel's deep cuts, which will continue into the next quarter.

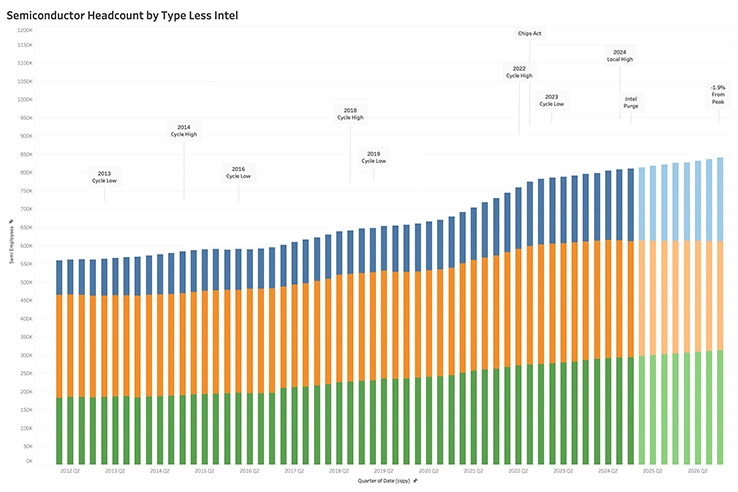

It is fair to assume that Intel is the single source of the problem, resulting from overhiring. While the decline is undoubtedly due to Intel's actions, the new growth trajectory remains the same if Intel is removed from the equation.

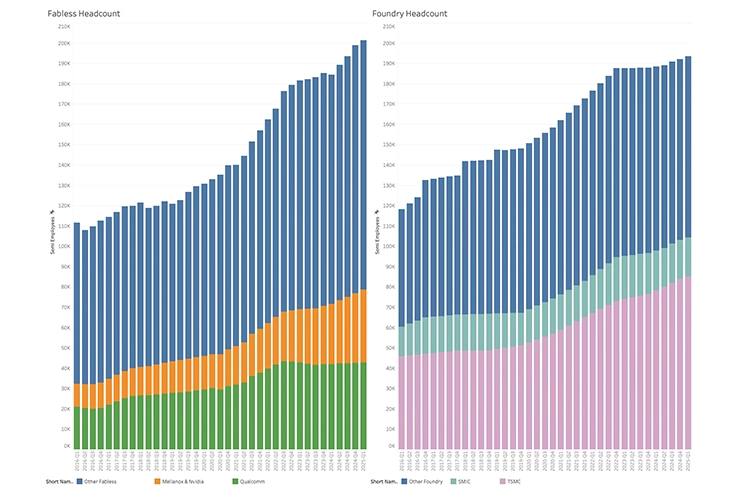

Another fair argument that could be raised is that this is due to the increasing impact of foundries on the semiconductor industry, and the headcount of foundries should be taken into account.

The plot below shows the combined headcount of semiconductor companies (delivering to the device market) and Semiconductor foundries (supplying the semiconductor companies).

Note that Q1-25 headcount is added to the plot.

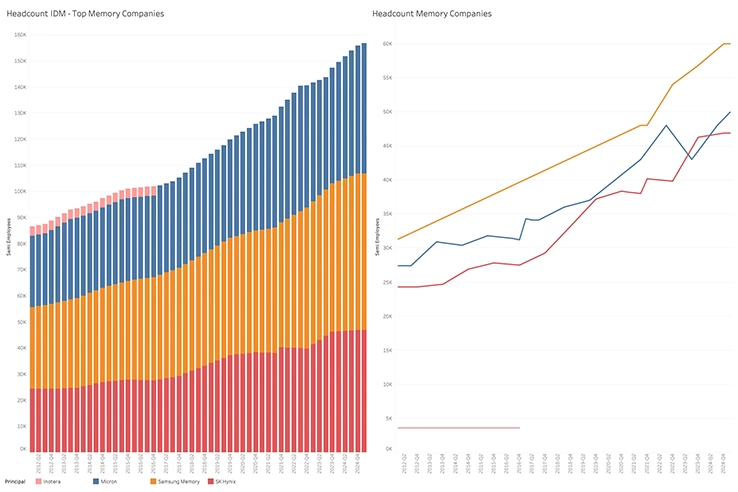

While hybrid headcount has been in decline, similar to the revenue decline experienced by hybrid companies, the IDM headcount grew until the Intel culling began. This is mainly due to memory companies that add headcount over time, even through cycles.

The latest increases are likely due to the rise in future capacity, as indicated by the increase in capital expenditures (CapEx) of the three leading memory companies.

For fabless companies, Nvidia's rise is apparent, although the dominant AI leader still has fewer employees than Qualcomm. I will examine productivity later, which will better demonstrate this dominance.

The foundry headcount also remained flat after the Chips Act was ratified, but TSMC's headcount has continued to increase steadily.

Interestingly, the headcount of SMIC has declined, which sounds somewhat counterintuitive.

While there is a change in the Semiconductor industry, it is not apparent what the cause is. It is time to dig deeper into the data.

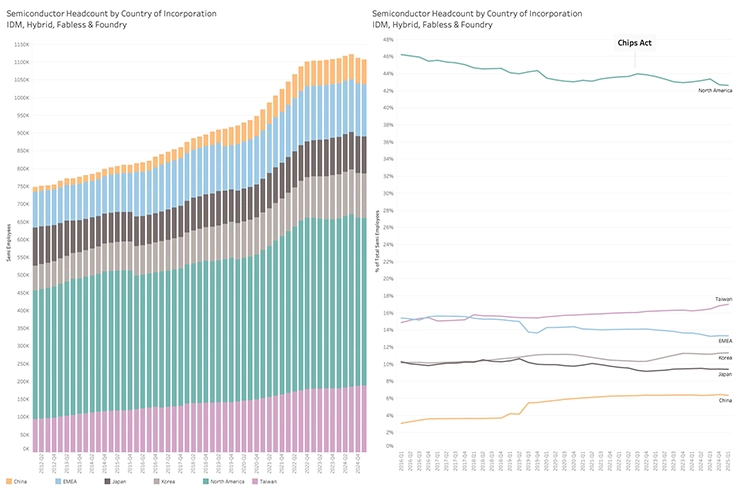

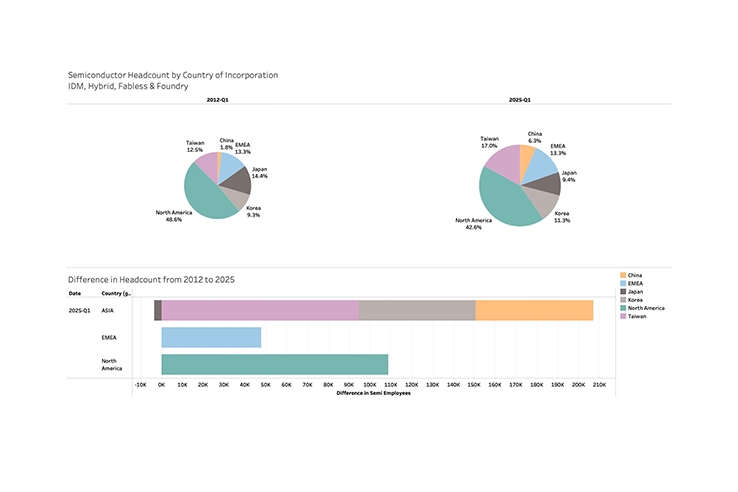

As many government interventions aim to prevent China from gaining access to key semiconductor technology in manufacturing and computing, it is essential to understand both the country of incorporation of the employer and the physical locations of employees at semiconductor companies.

Combining semiconductor companies and foundries for analysis might not always be productive, but from a headcount perspective, it makes sense. The foundry headcount refers to the outsourcing manufacturing headcount of fabless and hybrid semiconductor companies.

Apart from showing that the headcount by country of incorporation is very resilient, it can also be seen that US corporations have lost headcount share over time. Some of the share is lost due to additional offshoring of manufacturing to foundries in Taiwan.

Excluding the foundry headcount, the US lost 3% of its share during the period.

What is also apparent is that the Chinese headcount is growing, but it is not at a level that reflects the Chinese share of global revenue. WSTS numbers suggest that ASIA is 53% of Global Semiconductor revenue, while it only represents 43% of the visible headcount in the analysis. While most semiconductor and foundry headcount outside China works for public companies, this is not the case in China. While it is generally challenging to determine the share, this analysis offers some insights into the ratio between public and private companies.

My analysis indicates that the shadow headcount is approximately 140,000 employees, or about twice the visible number. In other words, we only see a third of the Chinese iceberg.

The Chinese headcount is also most likely the reason for the flattening of the Semiconductor headcount curve. The curve continues, but within Chinese private companies rather than in the open.

So, I am indeed one of a million, as the semiconductor device companies in the visible market have 914K employees.

Even without the shadow number, the combined headcount of the Asian companies has increased more than that of America and Europe.

Despite losing a share of the broader semiconductor market, US companies have increased their headcount by 110,000 over the period, while Europe has maintained its share. This contradicts the bottle cap memes that portray Europe as a technological dead end. Although this may not last, the headcount of European companies has been surprisingly resilient over the past decade.

Employees by location

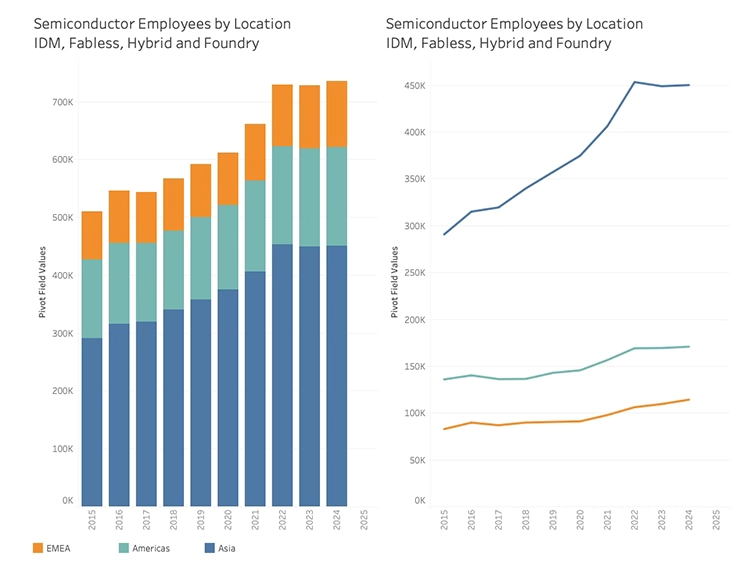

The Chipwars are indeed about the country of incorporation, but the physical location is critical. This data is more difficult to access, but I managed to resolve two-thirds of the visible headcount by physical location.

As I mentioned earlier, I include the foundry headcount in the analysis based on the same reasoning.

The analysis thus covers the largest semiconductor companies and foundries, with China being represented by SMIC only.

This result would surprise even a semiconductor consultant (just kidding - they get surprised by nothing). While the rise of semiconductor employment in Asia is expected, the continued growth of headcount in Europe is quite surprising.

Since 2015, the headcount in Europe has grown at a 3.6% CAGR, while the Americas' headcount has grown at a 2.6% CAGR. Asia has grown Semiconductor headcount by 5.5% CAGR in an industry that has grown by 8% over the cycle. The headcount in Asia took a break in 2023, once again coinciding with the ratification of the Chips Act. It did indeed have an impact.

As the Chips Act Agenda builds on the political belief system that Semiconductors are strategic and should be built in the US (there are now rumours that TSMC dies built in the US have to return to Taiwan for packaging), it has become important for companies to look American.

“Intel never left. We’ve been investing and innovating in the U.S. for over 50 years.” — Pat Gelsinger, Intel CEO

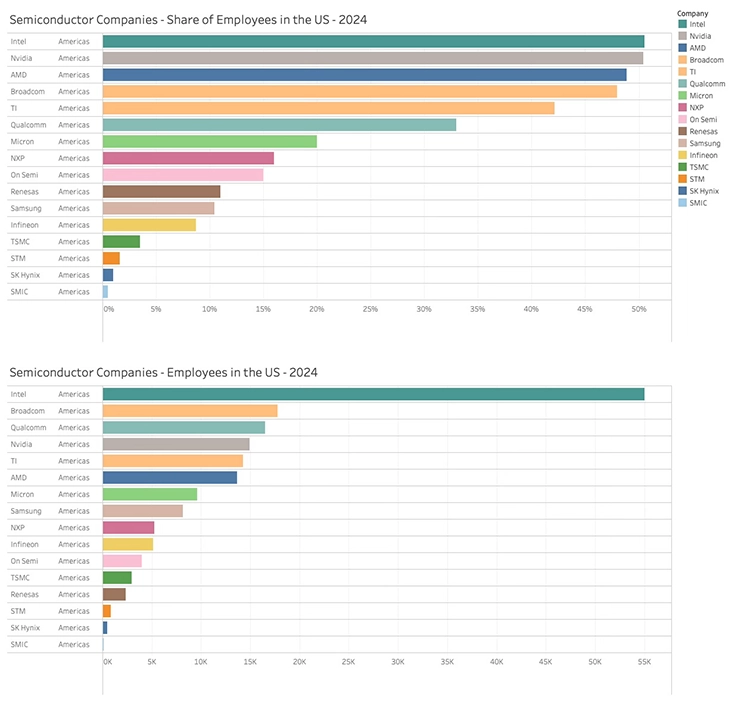

While it is slightly off track of the primary analysis, it is too tempting not to take a look at “How American” the semiconductor companies are from a headcount perspective.

Interestingly, only two of the major semiconductor companies have more than half of their employees in the US. While Intel is still the most “American” semiconductor company, it still has close to half of its employees outside the continent.

The most “American” foreign company is NXP, with 16% US employees, a higher share than On Semi, which claims to be “American”.

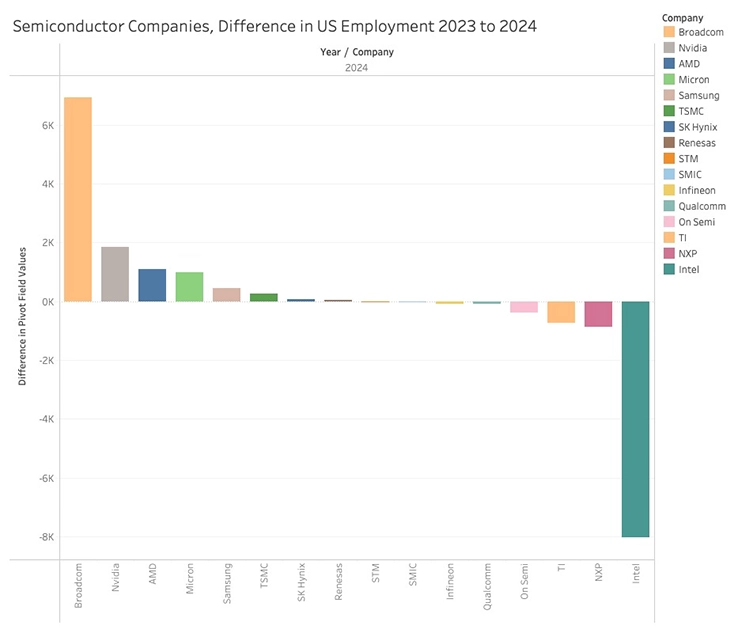

The footprint of the companies attracted to the US by Chips Act money is growing, but not yet at scale. The total difference in US Semiconductor employment of the largest companies has been embryonic.

This covers a decline in US-based Intel employees and a small growth in the rest of the Semiconductor companies. While it should have been finalised in 2023, some of the increase in Broadcom employees is likely due to the VMware acquisition.

Even with this potential uncertainty in the data, the verdict is clear: the impacts of the Chips Act on US employment are still in their embryonic stages, despite much fanfare.

Headcount Productivity

It would not be far-fetched to suggest that the decline in headcount growth could be linked to productivity growth. Better manufacturing tools and AI design of chips could have a positive impact on productivity, so fewer employees are needed.

As revenue is involved, my analysis returns to the headcount of Semiconductor device companies and excludes the foundries.

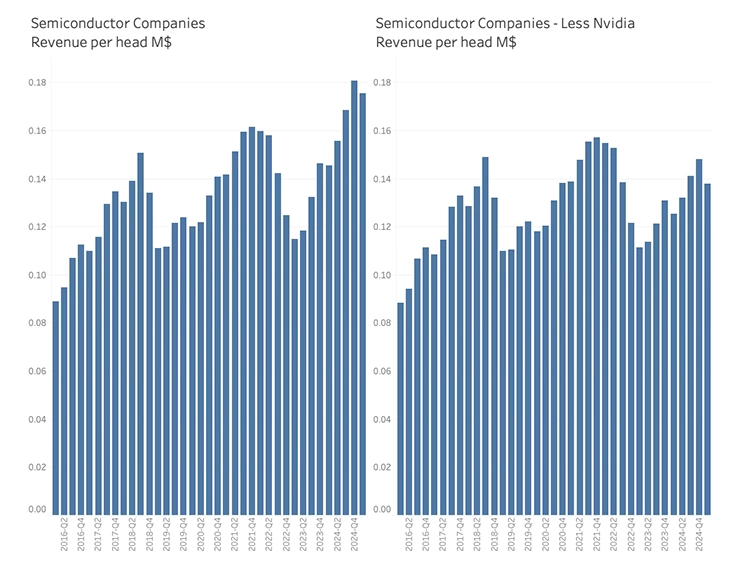

As Nvidia is moving the productivity needle quite dramatically at the moment, it is necessary to analyse productivity by headcount, both including and excluding Nvidia.

The analysis, excluding Nvidia, reveals that the productivity gain over time is not massive. The peak-to-peak productivity gain is 1.3% CAGR, while the trough-to-trough productivity gain is 0.3%.

Except for Nvidia, the industry is still relying on headcount for revenue growth.

It is already established that this semiconductor upcycle is driven by Nvidia, but this does not explain the underlying lack of headcount growth. If this were a regular cycle, Nvidia’s revenue would be on top of the revenue growth of the other semiconductor sectors rather than replacing it as it currently is doing.

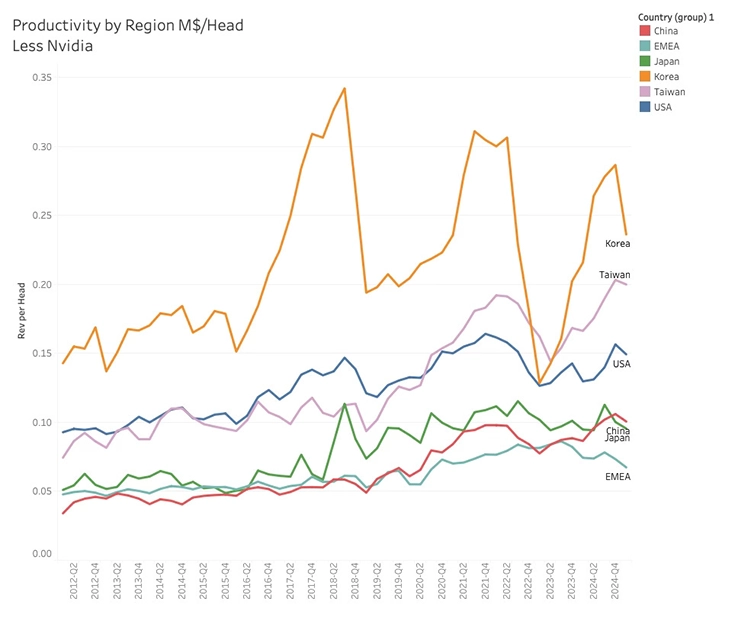

In the earlier analysis, the visible Chinese headcount was about one-third of the shadow headcount. To understand the impact on revenue, it is necessary to compare Chinese headcount productivity with that of the rest of the world.

While the three manufacturing models of semiconductor companies yield different results, with fabless having the highest revenue per employee and the hybrid model having the lowest, the productivity gains for the three models are reasonably similar over time. Although I have the data, it will not be considered in this analysis.

As can be seen, China is not exceptional in terms of size or productivity growth, which is also surprising, given that the semiconductor business model and manufacturing are very similar, irrespective of location. The Korean fluctuations are due to the high level of memory content in the country's revenue.

There is no indication that the productivity of the semiconductor industry has suddenly changed, although this can certainly happen in the future with the introduction of AI. While the upturn appears normal, it is entirely AI-driven and conceals the fact that all other markets are either flat or appear to be flat.

Over time, the industry headcount has been growing until the introduction of the Chips Act. While it is difficult to prove directly, the headcount is likely still growing, but the growth has shifted to China. It would be surprising if the two-thirds hidden headcount is not resulting in two-thirds hidden revenue.

This would correspond well with the rapid growth in Semiconductor tool sales to China since the Chips Act was ratified (The Latest Drivers and Trends in the Semiconductor Tools Market). Non-AI growth has shifted to China.

While it is not always an accurate science, a headcount analysis can generate a significant amount of insights into the development of the semiconductor industry. In this analysis, the focus has been on the headcount of the semiconductor companies and their foundry partners, while I have left the rest of the supply chain for another day.

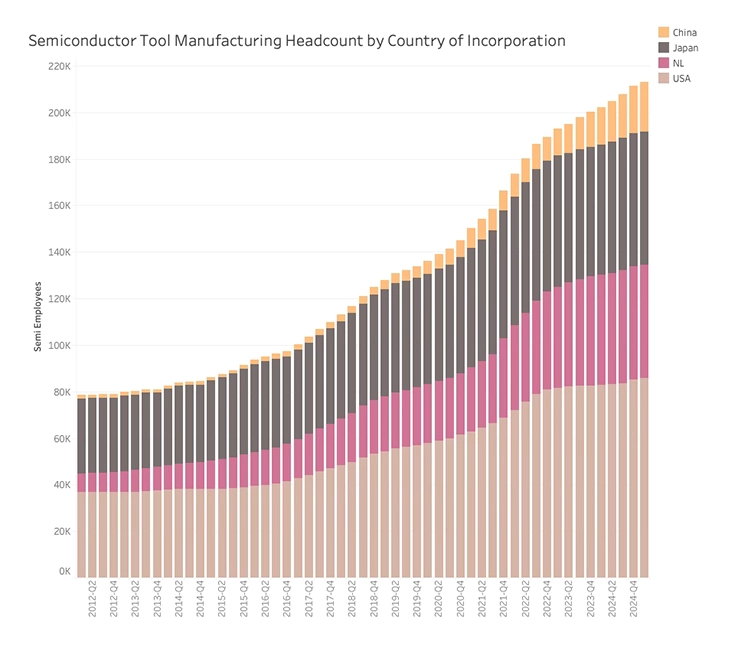

However, I will conclude this post with a chart showing the development of the headcount of the semiconductor tool manufacturing.

The analysis focuses on the tool manufacturing headcount, rather than the service or other elements of the tool companies. What is very obvious is that the tool companies’ headcount growth is at an entirely different level than that in the semiconductor industry. The headcount growth has been 8% CAGR since 2012, reflecting the overall revenue growth of the semiconductor industry. Why that is, is also a topic for another day, but I included the headcount for intelligence about the Chinese tool business.

While Chinese semiconductor companies have been purchasing 37% of all Western tools over the last two years, they have also been expanding their tool industry, resulting in a total of 39% of all tool sales.

Chinese tool manufacturers have increased their market share to 11.9% in Q1 2025, while their headcount accounts for less than 10% of the total. In other words, they are already more productive than their Western counterparts in terms of revenue.

Since the Chips Act was ratified, Western tool companies have grown their revenue by less than 10% CAGR, while Chinese tool manufacturers have grown their revenue by more than 24% CAGR.

Subsidies, Embargos and Tariffs have consequences, but rarely the intended ones.